Christopher Lawton stood in the dirt next to the first plot sold in Eatonton's Pine Grove Cemetery to make a point.

The unmarked grave of David Myrick, one of the wealthiest people in the middle Georgia town in the mid-1800s, was a far cry from the lavish lifestyle he and his wife, Polly, enjoyed during their lifetimes.

The unmarked grave of David Myrick, one of the wealthiest people in the middle Georgia town in the mid-1800s, was a far cry from the lavish lifestyle he and his wife, Polly, enjoyed during their lifetimes.

"How did the Myricks sustain such an elite existence?" he asked the high school students gathered with him.

The answer could be found in the documents they had been studying. One detailed the sale, in May of 1835, of a little boy on the courthouse steps.

"They sold a 7-year-old boy to pay for that," said Lawton, director of experiential learning for Putnam County Schools, as he gestured toward downtown Eatonton and the home where the Myricks lived. "How did his mother tell her little boy, 'I'm not going to see you anymore?'"

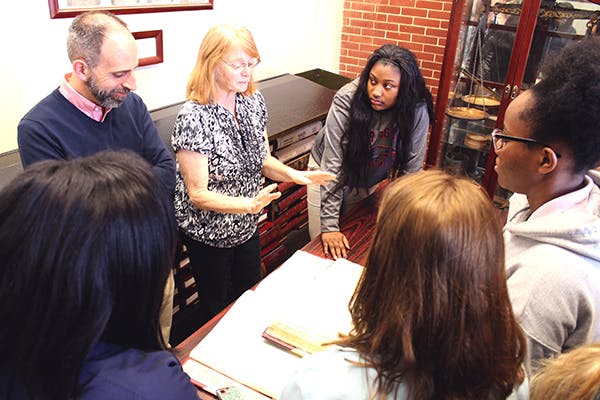

Lawton's story capped a morning of discovery for 14 students from Putnam County High School who are taking part in a multi-year project to archive documents and photos related to the county's African-American history. As part of the project, faculty and graduate students from the University of Georgia College of Education are helping to create curriculum that blends the literacy and history lessons gleaned from the research into classroom curriculum.

Originally begun through the Georgia Virtual History Project, of which Lawton is director and which is affiliated with UGA's Willson Center for Humanities and Arts, students are learning how to dig through 200-year-old records and catalog them for future use.

The project recently took on new legs thanks to a $100,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities awarded to the Willson Center. It represents a unique partnership between the Willson Center, the College of Education and the Putnam County Charter School System. The Willson Center and the College of Education have been engaged for the better part of a year in raising required matching funds for the grant, an effort that remains underway.

"Our partnership with T.J. Kopcha and the College of Education made this grant competitive," said Nicholas Allen, director of the Willson Center and Franklin Professor of English at UGA. "T.J.'s expertise in curriculum innovation and inclusivity added a new dynamism to the rich cultural history that the project addresses. One of the great gifts of working at a leading public research university like UGA is the ability to put together teams of brilliant people, and we have been very lucky to build a program that is a national leader in the public humanities thanks to the College of Education."

By discovering the documents, digitizing them and making them searchable, the students are creating a valuable database of family history that, until now, was virtually unknown.

"Photographs, deeds, letters—this stuff is out there and it's a piece of a puzzle. It's a story waiting to be told, and it represents someone's life," said Kopcha, associate professor in the College of Education's department of career and information studies. "Christopher and I have been working on this idea of digitizing history for a long time, and it's landed in a K-12 context."

"Photographs, deeds, letters—this stuff is out there and it's a piece of a puzzle. It's a story waiting to be told, and it represents someone's life," said Kopcha, associate professor in the College of Education's department of career and information studies. "Christopher and I have been working on this idea of digitizing history for a long time, and it's landed in a K-12 context."

A personal connection Students spent the earlier part of the morning learning about probate court and looking up the Myricks' records in the Putnam County Courthouse. But those documents, with their script handwriting and thick legal language, only tell a portion of a person's story.

From the courthouse, the group moved to the Myrick home located a few blocks from downtown and the cemetery. Standing in the overgrown front yard, Lawton held another Myrick family document that wasn't part of the courthouse collection. Found among a private collection in Eatonton, it was a photocopy of two of its pages listing the family's assets in the 1820s. Among land and household items, the second page held another type of list.

Hal—$550. Herod—$550. Abram—$550.

One by one, Lawton and the students read the 35 names from the list of slaves owned by the Myricks. Then he posed a question: When do you think was the last time those people's names had been said out loud?

Some students balked, joking that they had raised the spirits of the dead. But Lawton and history teacher Andrew Grodecki pointed to what was around them. "Who built this house? Slaves. Who set the bricks in the chimney? Slaves," added Lawton. "They lived here. They made this place. It belongs to them, too. So why hasn't anyone stood on this ground and said their names in nearly 200 years?"

"They weren't people," answered the students.

Community liaison Avis Williams, who had joined the students for the morning lesson, helped put the experience into a larger context. At the time the document was written, the children on the list did not belong to their parents. The names listed there were only the markers of property. For many, that name listed on a piece of paper was all that was left of their identity. "We just honored them by calling their names," she said. "It's all in a name, and we just honored them."

Community liaison Avis Williams, who had joined the students for the morning lesson, helped put the experience into a larger context. At the time the document was written, the children on the list did not belong to their parents. The names listed there were only the markers of property. For many, that name listed on a piece of paper was all that was left of their identity. "We just honored them by calling their names," she said. "It's all in a name, and we just honored them."

A new approach to learning Now in its fourth year, the project represents a larger initiative to re-think the way public education happens in Putnam County. "It's experiential, humanities-based, and tailored to the needs of rural students," said Kopcha. "Students aren't just learning history – they are learning that they are from a place that matters and that they matter to that place."

Grodecki recalled the story of a student who worked on the digitization project the previous year. In the midst of entering names into the database, she realized they were part of her family. "She said, 'These are my people.' If you're African-American and your family has been in Putnam County since before 1865, you could be the descendant of slaves."

At the time of emancipation in 1865, Putnam County was home to 7,000 blacks and 2,000 whites. While some courthouse records have been lost to fire and flooding, it's the white families that can still trace their family history; documentation of black families is less reliable, if it exists at all.

Over time, the students in Putnam County will help rectify that, as much as they can.

"And that's why this project matters," said Grodecki. "It's impactful stuff. When you're standing on the ground where these people lived, helping to share their stories with the world, it has meaning. This is how you learn."