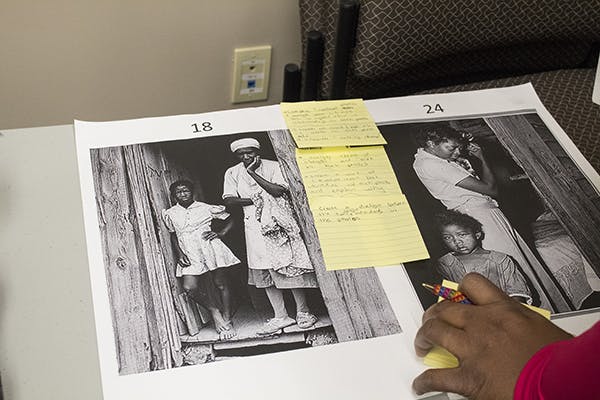

The black-and-white photos taped to the wall of the Putnam County Board of Education meeting room both depicted two generations of women, but each held their own story.

In one, a woman readies for church, while in the other an older woman is dressed for housework. In one, a little girl seems hushed as she watches the woman get ready to leave, while in the other a young girl stands barefoot at the doorstep, her hand resting on her hip.

When viewed through the lens of a teacher, these photographs from 1941 take even more meaning and evoke a series of questions. What other comparisons and contrasts can be made between them? How might a poem, such as Langston Hughes' "Life Ain't Been No Crystal Star," help students relate to the women in these photos? What can the images reveal about mid-twentieth century life in a poor, segregated community in rural Georgia? And, perhaps most importantly, how can they be used to create meaningful, place-based learning experiences in the classroom?

When viewed through the lens of a teacher, these photographs from 1941 take even more meaning and evoke a series of questions. What other comparisons and contrasts can be made between them? How might a poem, such as Langston Hughes' "Life Ain't Been No Crystal Star," help students relate to the women in these photos? What can the images reveal about mid-twentieth century life in a poor, segregated community in rural Georgia? And, perhaps most importantly, how can they be used to create meaningful, place-based learning experiences in the classroom?

These were just a few of the observations and questions that a team of Putnam County teachers came up with during a recent workshop with TJ Kopcha, associate professor of learning, design, and technology, and Beth Pitman, his doctoral student in the University of Georgia's College of Education. Together, they are building curriculum that connects Putnam students at all grade levels with these and other local photographs in the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

Kopcha, Pittman, and the Putnam County teachers are using the photographs to develop learning experiences such as researching the past through records in the local courthouse, creating oral history archives from local community members and even curating a future art show with the photos and information they gather. By aligning the photographs and the projects with content standards for K-12 classrooms, their work has a loftier goal: To provide teachers across the country with project-based learning opportunities that draw upon the rich historical resources publicly available in the National Archives.

The multi-year project is funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities that supports collaboration between Putnam County schools, UGA's College of Education and the Willson Center for Humanities and Arts. This school district-university partnership was the only pairing of its kind in the country to receive funding through the National Endowment for the Humanities.

"This grant allows us to bring an amazing team of scholars and teachers together to get students out from behind rows of desks and into the community," said Christopher Lawton, director of experiential learning for Putnam County Schools. "It's an opportunity for our best and brightest teachers to figure out how kids can learn what they need to learn, but do it through the lens of where they're from. This is how a community, its school system and a major university can come together to create change."

The project has potential on both a national and a local level, said Kopcha, and providing it in a project-based format helps students gain a deeper understanding of the content.

"There is compelling evidence that project-based learning can improve student outcomes. Students take ownership over their work, and that work is hands-on," he said. "This can lead to deeper engagement and understanding of content standards across a variety of content areas."

For Putnam County students, the photos they will be studying represent a specific time in their community's history that was nearly lost—and that adds even more meaning, he added. "The fact that these photos come from within the students' own community makes this approach even more compelling," said Kopcha. "Students are not just learning about history or math or science, but they are learning about their community in ways that typical classroom resources do not and cannot fully address."

The photographs, stored in the National Archives, were taken in May 1941 as part of a Works Progress Administration effort to document American farmland. This collection is predominantly black-and-white images of vast fields, devoid of people. But the photographer assigned to Putnam County was Irving Rusinow, who later went on to become an award-winning documentary maker and cinematographer. His photos of Putnam County are unlike any other in the collection, said Lawton—they are snapshots of lives.

"We have been given a gift with these photos," said Lawton, who discovered them in the National Archives years ago but, until the grant opportunity surfaced, didn't have a way to work them into the curriculum and tell their stories. All but one have general captions, leaving people and places largely unnamed. "I have been waiting for years to share these."

At the workshop, Lawton, Kopcha and Pittman laid out 85 of the photos and asked the teachers, ranging from elementary to high school levels, to pick one (or two) that spoke to them. They challenged the teachers to ask questions about the image and consider how these questions might fit into a lesson they are teaching.

For example, one image showed a roadside scene of cleared land, a new growth of trees, and a hand-painted sign reading, "When ye think not Jesus will come, ye be ready." The teacher who chose it took it in two directions. On the one hand, he said, it could be a lesson in ecology, noting the methods used to clear the land of the invasive sweetgum trees seen in the background. On the other hand, he felt the image and its message could be used to juxtapose lessons about the environment with religious idealism and viewpoints of how we care for the world around us.

For another teacher, an image of people leaving the Putnam County Courthouse evoked ideas for teaching quadratic angles, 3-D modeling, and a field trip to compare the old courthouse with how it looks today.

Then, she realized the image also included people—possibly a wedding party leaving the courthouse—and it added another dimension to the lessons she imagined. "A bunch of our students could be related to the people in these photos," said another teacher. "Wouldn't that be cool to be able to make that connection?"

By the end of the afternoon, the teachers had lists of lesson ideas and were tasked with taking the next steps: identify grade standards that will be addressed and plan what students will create as a result of the lesson and why. The teachers were also asked what support or resources they might need from UGA.

Over the next few months, they will work with Kopcha and Pittman, collaborating virtually on a weekly basis and meeting in person every month. They will come back together next summer to debrief and reflect on the challenge, as well as plan for the following year.

"This is going to allow us to build pieces of curriculum that are hyper-local," Lawton explained to the teachers. "It gives us a tool for you to do what you need to do, but also connect it to the idea that our kids know where they are from."