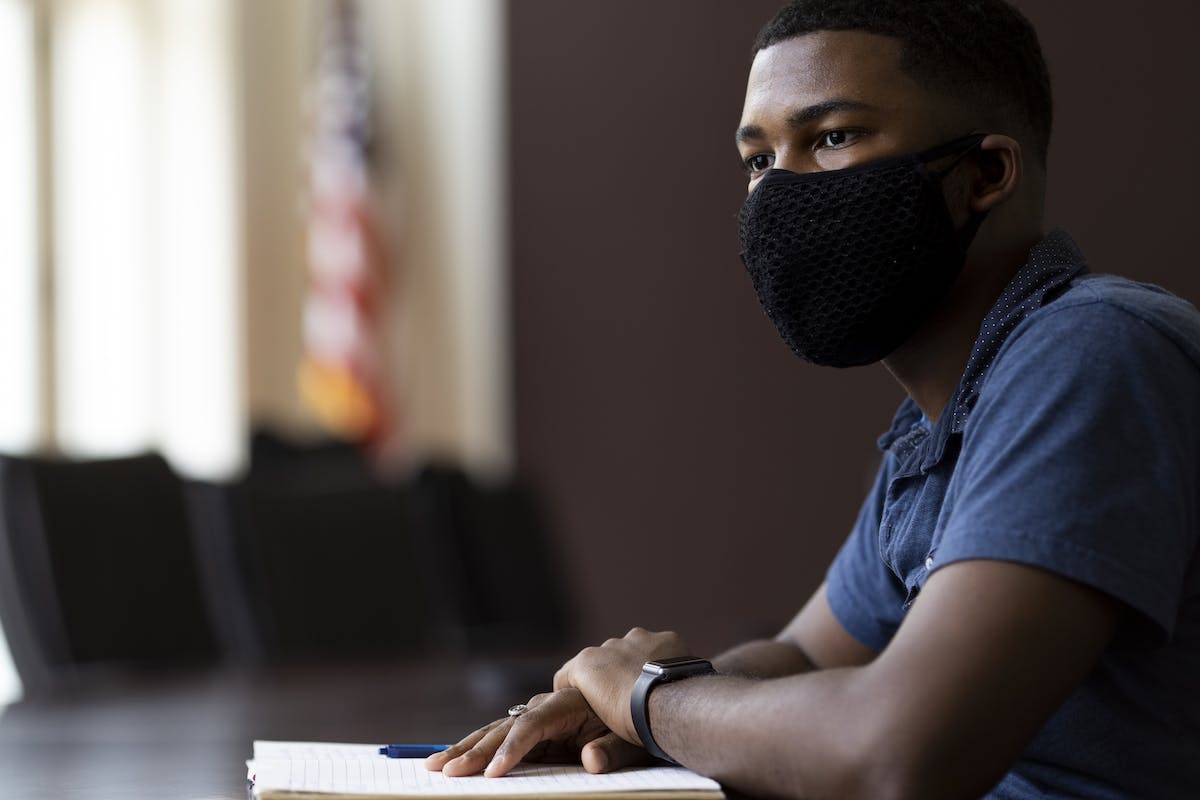

Ricky Belizaire (M.Ed. ‘21) loves every second of his work as a graduate assistant in the University of Georgia’s LGBT Resource Center.

A master’s student in college student affairs administration in the Mary Frances Early College of Education, he advises the LGBT student ambassadors and PRISM, a discussion group for queer and trans people of color. A lot of his work is in building community for UGA students—and making them feel connected.

Inclusivity is something he’s passionate about—it’s why he picked his master’s program. As an undergraduate in New Jersey, he was a member of his college’s diversity and inclusion board, interned with the dean of students and involved in Greek life.

Through mentors, he discovered the field of student affairs. UGA has one of the best student affairs master’s programs in the world. A native of Connecticut, Belizaire wanted something different for college. The school’s reputation plus Georgia’s warmer climate convinced him to move South.

“I wanted to learn at a place that would really challenge me and allow me to grow,” he said.

The power of y’all

One thing that surprised Belizaire was Southern culture. He’d heard of Southern hospitality but was skeptical.

‘You guys’ is inherently masculine centered, which I didn’t stop to consider enough when I was younger. This role as a graduate assistant has allowed me to be more aware of language."

The College Student Affairs Administration program

In his master’s program, he has learned leadership—how to lead a team and lead other people—skills he could easily translate to the nonprofit sector or corporate world.

He learned how to be a better communicator. “I don’t show up the same way I used to,” he said. “I listen to people. I listen to their needs. I assess what they might need and ask questions. I explore things other people might not. I really like to sit down with my students: What is going on, how can I really support you?”

He holds biweekly meetings with students and tries to go beyond asking about class, instead asking about their challenges and how he can help them meet those challenges.

“Who I am now is completely different than I was two years ago—because of my education,” he said. “I just see the world differently. I’m advocating for rights, advocating for people who don’t look like me, getting them support, not backing down. Two years ago, I would never openly discuss things and speak up. I didn’t feel like I had enough knowledge.”

The program gave him confidence so that he can speak up. But through his coursework and experience, he sees what students need—and tries to fill that need.

It’s how Q-mmunity Wednesdays came about.

Q-mmunity Wednesdays

When the pandemic hit, the LGBT Resource Center first worked to get its students immediate resources to combat food and housing insecurity and then quickly focused on student mental health. While the pandemic has been hard for everyone, they wanted to support students of color, queer and trans students—to make sure they were seen and heard.

Belizaire created Q-munnity Wednesdays to have an online safe space for queer students in crisis. He saw the need and volunteered to write the program proposal.

“We’re meeting students where they’re at virtually,” he said. “We have critical conversations so that students in crisis, in need of support can get those resources. We give them a virtual space to connect with others, to interact.”

Indeed, the pandemic flipped the way the LGBT Resource Center operated. Previously, the center held lots of in-person events to build community for students. Last year, the center switched to Zoom and social media. Belizaire and other staffers would post on social media every day to check in on their students. They went from 500 followers to 1,425 followers on Instagram—with lots of engagement.

“We need those interactions,” he said. “We’re all human and social by nature, and we need to be with people and need community.”

COVID-19 impact

Ultimately, COVID-19 made him think more about his students. He also took time to check in with himself, asking, “How am I doing?”

“If I’m not doing well, what does this mean for my students? How can I make sure they’re getting the help and support they need during this time?” he said.

Proudest accomplishment

But through all of the classes, one-on-one sessions with students and POSE marathons he holds for his PRISM group, he’s proudest that soon he’ll be a published author. He’s working on a book chapter for “Exploring Black College Men & Leadership Learning.” His chapter looks at transfer student experiences, specifically what their motivation is and what shapes their experience: mentors, communities of support or self-determination.

First generation

Beyond that, he says he has immense pride to be graduating with a master’s degree this May.

The son of Haitian immigrants, Belizaire is a first-generation college student who is the first in his family to live away on campus, and the first in his family to be getting a master’s degree.

The pandemic also changed some of his plans. Originally, he thought he’d want to work in Atlanta.

But when his dad got coronavirus last March, he realized how much family—and being close to family—meant. And after May graduation, he’ll be looking for jobs in the Connecticut-New York area near his family.