For Oksana Lushchevska (Ph.D. ’16), an alumna of the Mary Frances Early College of Education’s Department of Language and Literacy Education, the war in Ukraine hits home.

A native of Ukraine, she currently resides in Charlotte, North Carolina and has lived in the United States for 19 years. Lushchevska is the author of 44 children’s books and works as an independent scholar, translator and creative writing teacher. She also works with families and educators in Ukraine and the U.S. to help share each country’s cultures and promote peace.

‘Everything gray and very complex’

Before attending UGA for her doctorate, Lushchevska earned a master’s degree in education in Ukraine, as well as a master’s degree in Slavic literature and an M.A. certification in children’s literature from Penn State University.

During her Ph.D. program, she initiated “A Step Ahead: Getting Global with Ukrainian-English Picturebooks,” a bilingual picturebook project to foster conversations about identity, imagination and history for students in English- and Ukrainian-speaking communities. The project, which ran from 2014-18, published seven bilingual picturebooks.

During her Ph.D. program, she initiated “A Step Ahead: Getting Global with Ukrainian-English Picturebooks,” a bilingual picturebook project to foster conversations about identity, imagination and history for students in English- and Ukrainian-speaking communities. The project, which ran from 2014-18, published seven bilingual picturebooks.

“It was a project I put my heart and soul in,” she said.

More recently, she translated “How War Changed Rondo,” a book that details how three children living in the peaceful town of Rondo confront War and work together with their community to restore peace to their home. Written and illustrated by Ukrainian couple Romana Romanyshyn and Andriy Lesiv, the book received the 2022 Outstanding International Book award from the United States Board on Books for Young People.

While her books cover a variety of topics, her interests lie in concepts that touch the heart and soul, Ukrainian folklore and realistic fiction, which tackles complex topics that can be difficult for adults to explain to children—something a colleague of hers dubbed “everything gray and very complex.”

“I remember how one of my colleagues came to take a children’s literature class and he said, ‘well, everything is gray here. I though children’s literature is going to be easy, like black and white only, but this is like everything gray and very complex.’ Yes, I love everything gray, very complex. I’m in the middle,” she said.

Then and now

The current war in Ukraine stems back to late 2013, amid protests and several shifts in government power, followed by Russia annexing Crimea, a region in southern Ukraine, in 2014.

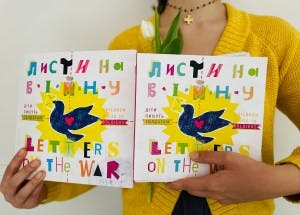

The first project Lushchevska worked on related to the war was translating “Letters on the War: Children Write to Soldiers / / Lysty na Viinu: Dity Pyshut Soldatam,” a bilingual collection of letters written by Ukrainian children to soldiers.

While the book was first published in 2015, Lushchevska said she’s been recommending it to educators who ask what books they should read to students about the current situation.

While the book was first published in 2015, Lushchevska said she’s been recommending it to educators who ask what books they should read to students about the current situation.

“Librarians were asking about this book because it’s really important to see how kids respond and to see that kids are the same everywhere, and they want the same things,” she said. “The voices of children are all about peace, all about friendship, all about being protected and having good days in general.”

In her research on children’s books about war, she said including experiences of war in real time and providing input to English-speaking countries can help teach important messages.

“Historical perspective helps a lot. It helps to construct the story because you are calm, you know what happened, you can bring a lot of feelings out, memories out, but it’s not like you have this raw emotional appeal when something is unfolding and something is happening,” she said.

“To me as a scholar, as a writer, it’s important to see what’s going on in the world and how to write about raw, central experience which is still going on,” Lushchevska said. “It’s not a historical scene, war is a kind of day-to-day scene for many countries, and you never know what’s going to happen.”

Giving back

This past spring, Lushchevska spoke with children living in Ukraine via Zoom several times a week to provide student support. Through those conversations, she said kids process the war differently across age groups and depending on their circumstances.

“It all depends on their level of safety, their level of moral understanding, their moral values and where they are,” she said. “They are very thankful that here in the U.S. there is huge support, and they feel that huge support from other countries in the world as well.”

Another benefit of sharing the books is that it introduces people around the world to Ukrainian culture. This sharing of culture will also help Ukrainians coming to the U.S. feel welcomed.

“I think it’s really important to show kids that here we know their culture and know their needs, and another thing is these kids can share their culture with kids in the U.S.,” she said.

“There is a belief in children’s literature that children’s books are couriers of peace and understanding, so I think it would be great for us to have more books from Ukraine here in the U.S. and to invite Ukrainian authors—we have a few here in the U.S. who can write in English—to a kind of fruitful and joyful cooperation, because that’s a big thing that we are going to observe the next two years.”